My Journey into Research and the Founding of CytoLogic Solutions

Welcome to the first post on the CytoLogic Solutions blog. I wanted to kick things off by sharing my journey—how I got into research, the path that led to founding CytoLogic Solutions (CLS), and a few thoughts on where things are headed.

This blog will mostly focus on side projects that I find interesting and want to share with the broader community. These could be new reagents, equipment, analysis tools, or even just a particularly insightful paper. I’ll also be commenting on new regulations, publishing trends, or emerging technologies—especially when I think they have the potential to solve real-world problems in immunology or clinical research.

A Rough Start

Like many kids, I did well in school without much effort—except in languages. Things changed drastically when both my parents passed away. I found myself juggling three jobs and sixth form, and I failed for the first time in my life. I started six A-Levels and left with two, neither with good grades.

Despite this, my computer science teacher, Mr. Steele, picked up the phone and called my university of choice. Thanks to his support, I was accepted to study Marine Biology at Heriot-Watt University, albeit starting in first year instead of the usual second year for English students entering Scottish universities.

Over my 4 years at Heriot-Watt university I worked hard, got my 2.1 Hon degree but I realised, after a very wet week in Oban, that the realities of a marine biologist’s life are not for me. But I really wanted to be a Professor, and I knew to do that I needed a Masters and a PhD.

From Arrows to Optics

Before I started applying for Master’s programmes, I wanted to spend a year working as a technician to make sure research was right for me. I applied for a technician position in the Physics department at the University of Edinburgh. I was sent a collection of papers that I didn’t really understand at the time, all on Forward Flux Sampling, and I was even more confused as to how they related to the microbiology technician role I was applying for.

I arrived for the interview and was greeted by Dr Rosalind Allen and Dr Gail Ferguson, who were seated across from me. I began talking about arrows and how they can be measured in flight as they head towards a target. I was nervous and felt like I was making a complete mess of it.

As it turns out, I had understood the papers I was sent. The point of the project was to link artificial genetic switches in bacteria to models using Forward Flux Sampling. The second interview was just with Rosalind, sitting casually in her office. At one point, a head popped around the door and there was some brief conversation about programme grants and funding for PhD studentships. Rosalind then handed my CV to Professor Wilson Poon, who took a quick glance and asked me if I wanted a PhD.

Sometimes, it’s just a matter of being in the right room at the right time.

I didn’t know if I wanted that PhD, but I knew I wanted a PhD, so I asked for some time to think it over. In the end, Rosalind and I agreed it would be better for me to take the technician position first, and then we could work together on developing a PhD question.

Finding My Niche

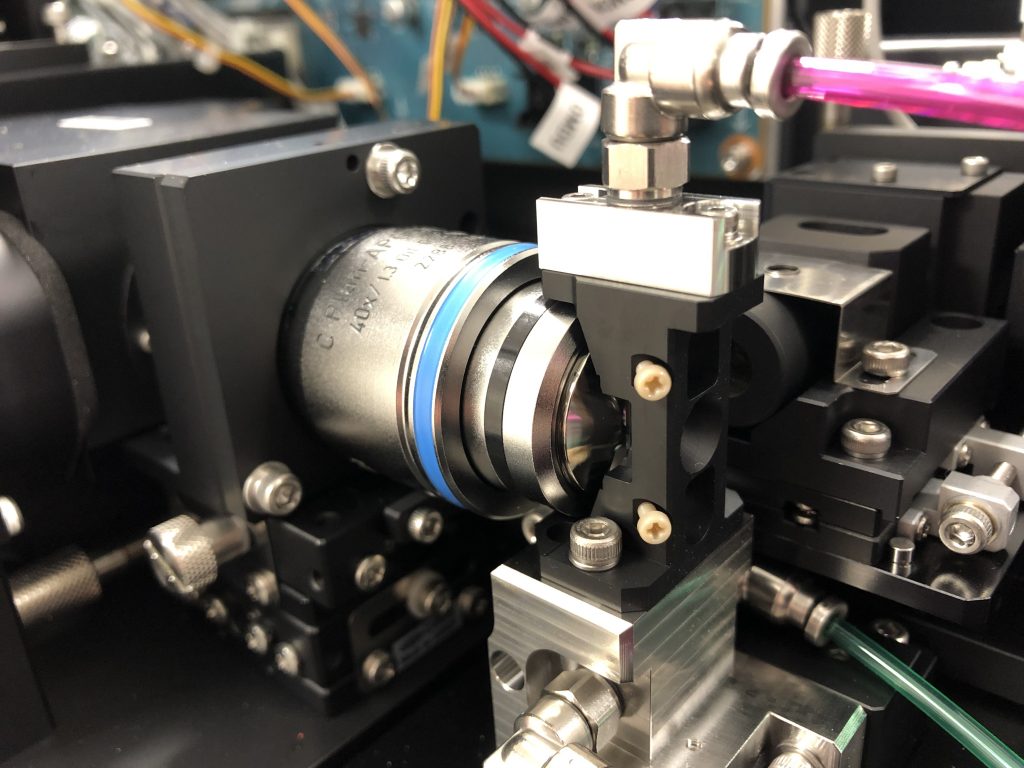

Over the next four years, I worked closely with Rosalind on a wide range of projects. I was incredibly fortunate to have a supervisor who was both curious and generous with intellectual freedom. It turned out that I was naturally drawn to (and good at) optics, microscopy, and imaging.

I still hadn’t completely let go of the idea of being a marine biologist, so I pitched a project imaging deep-sea bacteria under high pressure. That led to collaboration with Hugh Vass and the development of optical pressure cells for confocal microscopy. Using these, we were able to measure single photons in samples at pressures up to 60 MPa. Other projects included studying pressure-responsive metabolic pathways, designing pressure-sensitive genetic switches, and screening bacterial knockout libraries.

Postdoc Adventures: France, South Africa, and the UK

For my first PostDoc I moved to Montpellier, France with the promise that a small project on metabolic switches would lead to developing a high-pressure imaging system where we could use fluorescent correlation spectroscopy to measure how metabolism changes with increased pressure. After 18 months of wrangling with p-values and diminishing enthusiasm, I moved to Cape Town.

I had intended to leave academia altogether, but a phone call with Dr Marla Tuffin changed my mind. I joined her lab at the IMBM for a fantastic two-year postdoc. I worked on multiple projects, secured grants, began using flow cytometry, and met some truly inspiring people.

Family circumstances brought me back to the UK, where I joined the University of Oxford’s Department of Pharmacology MRC Unit (now the BNDU) as an imaging scientist under Professor Paul Bolam. There, I learned electron microscopy techniques and worked for a year until funding ran out.

That’s when I saw an opening at Imperial College London for a facilities manager role overseeing both flow cytometry and imaging. I applied—and haven’t looked back since.

High-Dimensional Flow and Clinical Immunology

I love imaging, but flow cytometry offered speed, both in data acquisition and analysis. It clicked for me quickly, just as tools like t-SNE and SPADE were emerging. I saw their potential and limitations when others didn’t. Working with world-class researchers daily made this period intellectually exhilarating.

In 2016, I moved to IAVI to run their clinical flow cytometry core facility at Imperial College, just as they purchased a new BD Symphony A5 (I think this was the seventh in the UK at the time). I really pushed that machine to its limits—and sometimes beyond. I’m pretty sure BD had my face on a “wanted: dead or alive” poster! I tested every component and compared it against the spec sheet, and I benchmarked it against machines from other manufacturers.

It wasn’t just testing for the sake of it. These were new machines; we didn’t know what we didn’t know about high-dimensional flow cytometry. No one in the community had answers, and I was rogue enough to start opening the big white boxes and testing bits.

There were also real scientific questions to be answered. I was leading a project to phenotype HIV patients from the Protocol C cohort who were able to control their viral load. These patients are rare—and even rarer now that HIV medicine is (thankfully) widespread in Africa. A 28-colour panel at the time was pushing it, but I did it twice: once for a phenotyping panel, and once for an ICS panel.

It was a hellish end to 2019, when almost 30 researchers engaged on the Viral Immune Profiling (VIP) project for nearly four months across five batches. We conducted functional ELISpots, ICS, phenotyping, and single-cell TCR-, BCR-, and RNA-seq. There was also a 44-plex MSD analysis, along with ELISAs, neutralisation assays, killing assays, and much more.

And then COVID hit.

Pivoting to Vaccines and Cancer Research

Lockdown didn’t last long. Our lab pivoted to vaccine development, partnering with Merck on a T cell vaccine programme, while Scripps focused on B cell responses. We developed assays, ran samples, and analysed data.

Alongside VIP, another project was quietly progressing—a comparison of HIV viral evolution and cancer neoantigen evolution. I collaborated with Dr James Reading, Professor Sergio Quezada, and Professor Charles Swanton on samples from the TracerX and Protocol C cohorts. I was initially hesitant to divert time, but James’s passion won me over.

Little did I know that this work would lead me to my next chapter.

From Research to Biotech

Sergio and Charlie had founded Achilles Therapeutics, focused on personalised neoantigen cancer therapies. After several recruiter calls (and a bit of convincing from James), I joined as a Principal Scientist in the Immune Monitoring team under Dr Emma Leire.

I was running the flow core for a growing biotech, I was developing assays and data analysis pipelines, I was involved in the clinical trials, and I could see my decisions having impact. During Emma’s maternity leave I was co-leading the team. When Emma returned, she stepped up to director and I was officially given my own team. It was a very exciting time.

There were also challenges, one that took a long time to overcome was the addition of peptide-MHC dextramers into a large phenotyping assay. It all came down to cost-benefit analysis – we were seeing reactivity in the product for up to 94 peptides and we simply couldn’t justify the cost of running that many peptides for all 6 HLA alleles. It took a lot of back-and-forth to get agreement on using a series of pre-screening ICS assays with MHC blocking antibodies so that we could narrow down the HLA and peptides to be tested.

Strategy is Key

Leading the data and assay side of the immune monitoring team meant that all patient data flowed through me. In most cases I saw the data before anyone else, single cell sequencing being the only exception. This meant that I knew the ATL001 clinical trial was going to fail long before anyone else. My strategy was to start to develop my teams R&D capabilities. Achilles had a long runway at that time but had reduced R&D spend to allow for the trial to be completed. I wanted my team to fill that gap and position us so that we could ramp up when the decision to take other assets forward was made. There were several projects in the R&D teams that could have born results, and I made sure my team was able and willing to contribute to any of them.

When the decision was made, it was not the decision I was expecting. The board decided to shut down the whole company rather than just the clinical trials. A year of planning was nipped in the bud in a 30-minute meeting. But that is how it goes in industry.

The team did a great job closing out their required parts of the clinical trial, doing all the archiving and equipment shutdown. I could not have been more proud of them pulling together in a hard time and doing what was needed.

Starting CytoLogic Solutions

After Achilles, I took time to reflect. Since my time managing core facilities at Imperial, I’ve known that I possess a rare blend of expertise that bridges R&D and clinical practice. I began consulting on data analysis and panel design—and quickly realised I could offer even more.

A conversation with Derek Davies finally gave me the push I needed to launch CytoLogic Solutions.

In the next blog post, I’ll share what CLS can do for you. Stay tuned.

Leave a Reply